Blog Posts

Thoughts on life, writing, art, and health.

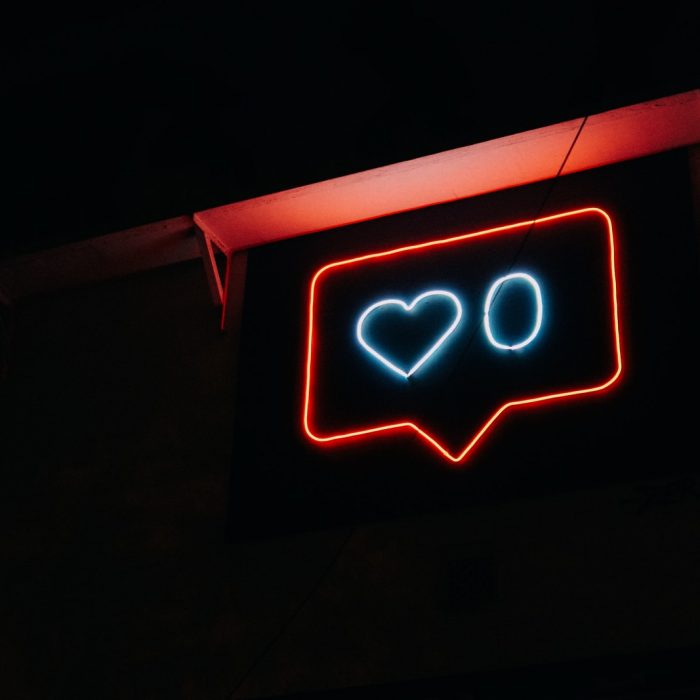

In memoriam: Show-and-tell on the Internet

This post does not aim to moralize; instead, it eulogizes.

At the end of February, I tore through Emma Newman’s Planetfall series. I had read the first book, Planetfall, back in June 2024 and waited on my library to get audiobook copies of After Atlas, Before Mars, and Atlas Alone (this was also the reading order I did). And as is typical for me, I looked up Newman’s presence online to get to know her a little bit more and see if she had any upcoming publications I could get my hands on.

In the process, I found her blog and rejoiced. I love reading blogs! Especially from writers when they post their thoughts, rather than focusing on an event announcement feed!

She posted to her blog in January 2025 about a topic that has plagued me since I was a teenager: the enshittification of the Internet via social media platforms.

Back then, I used to get up in the morning and be excited about seeing whether anyone had commented on my latest post or piece of flash fiction! I used to feel like I was walking down a virtual street and saying ‘good morning’ to people when I saw familiar names in the comments and replied to them. It feels like another lifetime. Another world. Now I fire up my computer like someone checking on a strange noise coming from downstairs. It will probably all be fine, but sometimes, there’s someone horrible right there. And even when there aren’t, there are horrible people screaming through the windows while I chuckle at wholesome Star Trek: TNG memes.

At the risk of being an old nostalgic gen Xer, the internet was enjoyable for me back then. And then… then we started posting the links to our blogs on Twitter and Facebook. And for a time, it was good. We had that ‘virtual water-cooler’ thing going on. New people found our blogs. We found new blogs too.

Then, the Fire Nation attacked.

“It’s time to rebuild” — Emma Newman, 12 Jan, 2025.

As a millennial, I have spent the majority of my life with computers and the Internet. I joined Twitter when I was around 16 years old. I had blogs before that, chronically my high school blunder years. (A public diary talking about my crushes? Of course! Why not? I didn’t post my surname or my home address, so there was relative safety and anonymity.

What social media took from me

The Internet felt so personal. It felt composed of real humans making real things and sharing real thoughts. It was like a meandering show-and-tell session. I could read blog posts about someone studying college courses in Australia. I could browse pictures of someone’s trip to Edinburgh. I could learn how to animate a custom avatar for Neopets from someone with only a username and a short tutorial.

We bonded over interests or simply passing through as we clicked affiliate links. Not the kind where someone gets a commission, but the “Affiliates” where site owners would link to your site with a 31 x 88 pixel button, usually animated and matching the aesthetic of your website at the time. We’d sign guestbooks and participate in Site of the Month events.

“I used to feel like I was walking down a virtual street and saying ‘good morning’ to people,” writes Newman, and she’s right.

But now, it’s like we’ve been pushed into night clubs, bars, and social venues that slowly—exponentially—expanded into megalopolis sizes. The majority of these clubs require some sort of ID (a login, in social media’s case) to be able to talk to other patrons, or even to step into the venue. Only with company buyouts can we use the same ID at different clubs. Facebook to Instagram to Threads, etc. It’s much harder to pass through.

Some social media sites call themselves, or have been called by others, “microblogging” sites. But it’s really not the same. Microblogging on social media is the equivalent of standing up at an open mic at one of the mega-venue clubs. Maybe over time or with a stellar performance, you’ll build up an audience who comes back. You can distribute business cards to tell people you have a smaller, more private venue they can visit you at (such as your website or email newsletter). But for the millions of us sharing our voices, we’ll get a few sideways glances, an errant cheer, and then the audience’s attention moves away, forgoing the business card and forgetting we exist.

Our presence in the social media mega-venue is transient. We don’t clock in like a job. We don’t announce when you can next expect to hear from us. We don’t have a dedicated space for circle time to show and tell. We pop in to post, and sometimes the mega-venue will fling our post to a new audience at a different time, gaining traction on something months-old and expanding our community.

Or, as is more common in my experience, it flings the post to a pit of rapid bots, trolls, and bigots who will spew misogyny and queerphobia at me.

Social media isn’t a safe space for me. I approach it with trepidation.

What social media gave me

It did take from me. I joined Twitter and Facebook when I was a teenager. Now, in my 30s, I have tried to limit my presence on those sites and erase my data to the best of my ability. My memories and time were taken from me. Social media took my attention, engagement, spare time, and data. I can never get back the literal years I have wasted scrolling or posting. As Newman also expressed, I have become a lurker in my online spaces too. I sometimes post on Threads. I have a few private chats on Instagram and Meta where we share funny videos or tell each other news. Even now, I count YouTube as a social media platform first and a video-hosting space second, and I’ve found myself falling into the trap of enraged engagement. I am embarrassed by what data these companies have on me and their intimate knowledge of how to push my buttons to get me to tap away on my keyboard.

This wasn’t a one-sided exchange where I graciously handed over my mental faculties. Social media gave something to me too: a low-key gambling addiction.

Every time I log on to social media, whether it’s based on text, images, or videos, I’m gambling. The algorithms randomly show me content, and some days it’s supremely entertaining. But when I’ve spent too long scrolling through funny skits and clips about mental health, the algorithm starts to scramble for new ideas. It can’t keep up with how quickly I pull the lever on the Content Slot Machine. I get random “Get Ready With Me” clips from teenagers. For a time, YouTube was plagued with softcore porn in its Shorts video section. I’m constantly shown nail art livestreams, likely because I subscribed to a single nail art channel on YouTube but haven’t explored the niche further.

Social media tries to put me in a box so that their algorithms can personalize to me. I turn off all personalized ads (as well as using two adblockers on my computer, and one browser with adblocking on my phone). The algorithms sometimes don’t know what to do with me because my interests change so frequently.

I’m a mood reader. I’m a mood watcher. I’m a mood-based consumer. My grocery shopping is primarily cravings and frozen food I can keep for months when the craving strikes again. (I’m not in a sandwich phase right now, for example, so I have my sandwich buns wrapped and frozen until I’m in that phase again.)

Social media doesn’t facilitate my mood-based consumption. The Blogging Days of Yore, however, did. I could bounce around between blogs and websites focused on different content. For a long time as a teenager, I was interested in graphic design and loved browsing “resource websites” that had resources for graphic design—fonts, brushes for Paint Shop Pro and Photoshop brushes,, macros, PNGs, written tutorials to create an icon or animation, you name it. Those website owners posted content so that we could enjoy the hobby together for free.

Once we joined the megavenue, the club owners encouraged us to be advertisers and then called us “content creators” and “influencers.”

From sharing to selling

The Internet used to be like a digital show and tell. We would make a silly website just for laughs or to share something we thought was cool. We’d join a blogging site to post a semi-public diary. We’d show people photos from our hikes and tell them about our days.

Then, we started getting asked why we showed, or told, or shared; they wanted us to rationalize the time and money we spent sharing: “What’s your brand? Do you have a niche? How do you make money from that? Would you sponsor a product? What about making a membership?”

We got pressured into explaining how we obtained the thing we were showing: “Can you do a tutorial? How did you make that? What tool are you using? How to do a thing in this many steps…”

If we entertained, now we needed to build up a fanbase like a production company and stick to a schedule to retain viewership in order to get money from ad clicks.

All of our behaviours needed to be justified through education or profit. If we didn’t want to educate—I will defend every artist’s right to show without teaching—and we didn’t want to profit, then people questioned why we put it online in the first place. “What’s the point of putting up a piece of art if the artist won’t teach me how to make my own or they aren’t selling prints of it?”

I got sucked into this trap too. I’ve felt a pressure, akin to the atmospheric pressure—sourceless, heavy, expansive—to follow suit with my blog. It’s why I’ve rarely posted; I struggled to see the value in my words when “successful” blogs were monetizing, advertising, sponsoring, teaching, and generally participating in a financial exchange with their readers and viewers. Mine wasn’t. Was mine failing because it wasn’t? I pay money each year to keep this space, but because I don’t profit from it, I must be wasting resources.

All I’ve ever wanted is to express myself. Use my voice. Be heard and seen.

It’s a core human need to want that, and we’re losing it online.

In therapy this year, I’ve commonly mentioned that being seen—literally being seen by other people, or having any attention on me—feels like being scrutinized. The root of this mindset comes from years of being bullied, harassed, and abused in person. Lately, though, I see how it occurs online. Spending over 15 years on the Internet has put me up to a lot of scrutiny, and most of it wasn’t valuable or constructive.

Recently, I ping-ponged around my YouTube recommendations and subscriptions, listlessly wondering what I wanted to watch. I would start one video, get an “ick,” and switch to another video… Only to re-experience the feelings. Everything presented to me—whether it was plucked by YouTube’s enigmatic algorithm or uploaded by a channel I chose to subscribe to—was a transaction. I provide my time, they provide me knowledge.

I ended up closing YouTube and taking a nap instead. I was tired of feeling inadequate. I was tired of information overload. “How to make your to-do list more effective. How to live better. n ways to improve a system that you’re not even using right now because you’re overwhelmed with strangers’ opinions and advice.”

Like private property, the Internet doesn’t permit loitering as much as it used to.

Don’t share: Sell, teach, or lecture instead

I’m seeking a quippy way to turn “show and tell” into “teach and sell”; that’s how the Internet feels now. If I want to show something, I better be doing it to educate someone or make money off them. If I’m consuming content, I better be prepared to learn or buy. If I’m posting online at all, I need to be prepared to read people lecturing me on how I’m wrong or bullying me because they hate who I am.

We suffer through information overload because we are trying to absorb all the knowledge that people are sharing, or we’re getting through 10-second, 30-second, or 6o-second skits, condensed to give us as much dopamine (through pleasure or anger) in the short span of time allocated to us by the social media platform. We struggle to find peaceful existence here, just chatting, just being.

Unsolicited advice is nearly universally annoying. So why do I opt into it with social media content? (Answer: Because I feel like I’m not good enough, and maybe the people teaching and selling online have a solution for me to feel better, and maybe it’s better than the attempts coming from my brain.)

Everyone has an opinion, including me—which is why I still have a blog and have tried social media. But on social media, in the megavenue, a user will post an excerpt of their life, and it’ll go viral. Next thing they know, hundreds of comments weigh in: questions, criticism, hatred, derision, tips, spam, bots, arguments.

I mourn the days I felt excitement reading the comments from bloggers and site owners across the world; I still keep up with some of the bloggers I used to “return comments” to, still tuned in from a lurker’s perch as they post about their lives in Australia or Europe or Japan.

Now, “Don’t read the comments” is a simple piece of advice for Internet users to follow if they want to protect their peace.

Even with the whole world at my fingertips, I feel lonely. I miss the friendships and community I had in the 2000s and 2010s, right before the social media and HQ camera smartphone boom of 2014. The Internet feels too big now, like every day, I’m walking into Canadian National Exhibition and half the vendors change every hour. It’s too much. I want my classroom-sized community back so that we can sit on the carpet and take turns with show-and-tell.

Our curious wandering has been replaced by gambled scrolling for anger or joy.

Comments

No Comments